published in: "Boston Evening Transcript" Oct. 31., 1896

The American physicist Robert W. Wood reports flight attempts with Lilienthal's Big Biplane on the Gollenberg in Stölln. Only one week later Lilienthal had a deadly crash at the same place. Wood took three pictures of Lilienthal's flights.

Lilienthal's Last Flights

A Thrilling Account by a Brother Aeronaut.

How Otto Lilienthal Started His Machine - A Picture of Him Fifty Feet in the Air - The Fatal "Scaling" of the Aeroplane - Our Correspondent's Success in a Flying Trip.

[Special Correspondence of the Transcript.]

London, Oct. 16.

On Saturday, Aug. 8, I received a letter from Otto Lilienthal, asking me to accompany him on the following day to the Rhinow Mountains, a range of high, barren hills some one hundred miles north of Berlin, where he was in the habit of exercising every Sunday with his flying machine. Being exceedingly busy with preparations for a trip to Siberia I was unable to go, and was spared the ordeal of witnessing the dreadful accident which caused his death, the news of which reached Berlin the following evening.

The readers of the Transcript will doubtless be interested in an account of the last flights of the fearless experimenter, which I witnessed the previous Sunday, and also, perhaps, in hearing of my own experience with the machine.

Herr Lilienthal had asked me to visit his engine factory in Berlin, where his flying machines are built, and it was here that I first became really acquainted with him. A small corner was given over wholly to the "Flug-Apparat" and here I found a number of men at work upon a new pair of enormous wings of more than 25 square yards superficial area. Of this machine he had great hopes, and explained every detail of its construction, little realizing that he was destined never to put it to actual test.

On the following Sunday I met him by appointment at the Lehrter station in Berlin. He was accompanied by his fourteen-year-old son, whom he always took with him, and a manservant to assist in putting the machine together. We steamed out of the city and across the flat green fields just as the sun was rising, and after a ride of a couple of hours alighted at Neustadt on the Dosse. Here we were met by a comfortable farm wagon and driven over the twenty-odd miles which lie between Rhinow and the railroad. A brisk wind was blowing, and the storks were sailing over the fields on each side of the road in search for food for their young on the chimney-tops. Them he watched with great interest, calling them his teachers, and drawing my attention to the various methods practised by them in preserving their equilibrium when flying and alighting, which I had never noticed before. We had a hurried lunch in the little inn at Rhinow, where his arrival always causes a hum of excitement among the peasants; the flying machine was brought out of the barn, and loaded on the wagon, and we drove away to the mountains, which are two or three miles from the village

A more ideal spot for flying could hardly be conceived. Rising abruptly from the level fields is a long range of high, rounded hills, varying from one to three hundred feet in height and thickly carpeted with grass and deep, spongy moss. The slopes vary in steepness and face all possible points of the compass, so that one can always find a suitable declivity facing the wind.

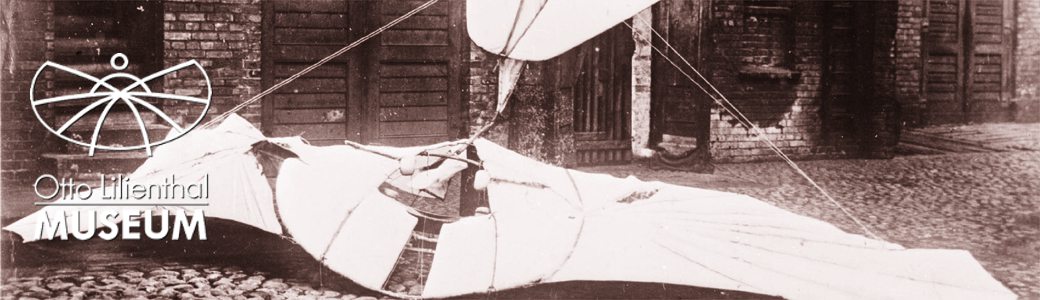

The machine was laid out on the grass and put together. It was one of the new models, consisting of two large lateral wings measuring twenty feet from tip to tip, and an upper wing or aeroplane. The material was thin, strong cotton cloth, tightly stretched on a frame of bamboo. A rectangular wooden frame which fitted around the body a little above the waist supported these wings and the duplex tail, consisting of a horizontal and vertical wing joined together on the end of a curved bamboo pole in the tear of the machine. The upper aeroplane was supported some six feet above by means of two vertical rods of bamboo, and firmly fixed by a great number of tightly stretched strings or guys. So perfectly was the machine fitted together that it was impossible to find a single loose cord or brace, and the cloth was everywhere under such tension that the whole machine rang like a drum when rapped with the knuckles. As it lay on the grass in the bright sunshine with its twenty-four square yards of snow-white cloth spread before you, you felt as if the flying age was really commencing. Here was a flying machine, not constructed by a crank, to be seen at a country fair at ten cents a head, or to furnish material for encyclopaedia articles on aerial navigation, but by an engineer of ability; and embodying the results of eight years of successful experimenting. A machine not made to look at but to fly with.

We carried it to the top of the hill, and Lilienthal took his place

in the frame, lifting the machine from the ground. He was dressed in

a flannel shirt and knickerbockers, the knees of which were thickly

padded to lessen the shock in case of a too rapid descent, for in such

an emergency he had learned to drop instantly to his knees after striking

with his feet, thus dividing the collision with the earth into two

sections arid preventing injury or strain to the machine.

I took my place considerably below him by my camera, and waited anxiously

for the start: he faced the wind and stood like an athlete waiting

for the starting pistol. Presently the breeze freshened a little; he

took three rapid steps forward and was instantly lifted from the ground,

sailing off nearly horizontally from the summit. He went over my head

at a terrific pace, at an elevation of about fifty feet, the wind playing

wild tunes on the tense cordage of the machine, and was past me before

I had time to train the camera on him.

Suddenly he swerved to the left, somewhat obliquely to the wind, and then came what may have been a forerunner of the disaster of the next Sunday. It happened so quickly and I was so excited, at the moment that I did not quite grasp exactly what happened, but the apparatus tipped sideways as if a sudden gust had got under the left wing. For a moment I could see the top of the aeroplane, and then with a powerful throw of his legs he brought the machine once more on an even keel, and sailed away below me across the fields at the bottom, kicking at the tops of the haycocks as he passed over them. When within a foot of the ground he threw his legs forward, and notwithstanding its great velocity the machine stopped instantly, its front turning up allowing the wind to strike under the wings, and he dropped lightly to the earth. I ran after him and found him quite breathless from excitement and the exertion. He said: "Did you see that? I thought for a moment it was all up with me. I tipped so, then so, and I threw out my legs thus and righted it. I have learned something new; I learn something new each time."

Though I had read many articles about Lilienthal, and had seen number less photographs of him in the air, I had formed no idea of the perfection to which he had brought his invention, or of the precision with which he managed it. I have seen high dives and parachute jumps from balloons, and many other feats of skill and daring, but I have never witnessed anything that strung the nerves to such a pitch of excitement or awakened such a feeling of enthusiasm and admiration as the wild fearless rush of Otto Lilienthal through the air. The spectacle of a man supported on huge white wings, moving high above you at race horse speed, combined with the weird hum of the wind through the cords of the machine, produces an impression that can never be forgotten.

A few moments' rest were necessary before carrying the machine once more to the hilltop, and we sat on the grass and discussed the incidents of the first flight. The grasshoppers clicked about on the cloth wings, and Lilienthal laughed at them, and said that they loved to jump about on the smooth white surface, that they were his only passengers and he frequently heard them hopping about on his machine when he was in the air. The wind had freshened a trifle and a shower was seen coming across the plain. We crawled under the wings, together with a swarm of peasant children who had flocked from the neighboring farms to watch "Die Weiße Fledermaus", and kept quite dry during the cloud-burst. The sun came out presently, and by the time we had reached the top of the hill the wings were quite dry. Once more he took his place in the frame and sailed away, the children running screaming after him down the steep hillside and falling over each other in their excitement. Of this flight and the subsequent ones, I was fortunate enough to secure some excellent pictures, the last ones that were ever taken of the man.

Towards the end of the afternoon, after witnessing perhaps half a score of flights, and observing carefully how he preserved his equilibrium, I managed to screw up courage enough to try the machine. We carried it a dozen yards or so up the hillside, and I stepped into the frame and lifted the apparatus from the ground. The first feeling is one of utter helplessness. The machine weighs about forty pounds, and the enormous surface spread to the wind, combined with the leverage of ten-foot wings, makes it quite difficult to hold. It rocks and tips from side to side with every puff of air, and you have to exert your entire strength to keep it level. Lilienthal cautioned me especially against letting the apparatus dive forward and downward, which is caused by the wind's striking the upper surface of the wings and is the commonest disaster which the novice meets with. The tendency is checked by throwing the legs forward, as in alighting, which brings the machine up into the wind and checks its forward motion. As you stand in the frame your elbows are at your side, the forearms are horizontal, and your hands grasp one of the horizontal cross-braces. The weight of the machine rests in the angle of the elbow joints. In the air, when you are supported by the wings, your weight is carried on the vertical upper arms and by pads which come under the shoulders, the legs and lower part of the body swinging free below.

I stood still facing the wind for a few moments, to accustom myself to feeling of the machine, and then Lilienthal gave the word to advance. I ran slowly against the wind, the weight of the machine lightening with each step, and presently felt the lifting force. The next instant my feet were off the ground; I was sliding down the aerial incline a foot or two from the ground. The apparatus tipped from side to side a good deal, hut I managed to land safely, much to my satisfaction, and immediately determined to order a machine for myself and learn to fly. The feeling is most delightful and wholly indescribable. The body being supported from above, with no weights or strain on the legs, the feeling is as if gravitation has been annihilated, although the truth of the matter is that it hangs from the machine in a rather awkward and wearying position. My second attempt was not so successful, the wind getting under the left-hand wing and tipping the machine until the tip of the other wing dragged on the ground. No damage was done, how-ever, and I felt quite satisfied with my first attempt.

On the way back Herr Lilienthal talked about his experiments and his plans for the future. Certain features of his machine he has patented, though his experiments have been made without any money-making view. The machines cost about 500 marks or $ 125 to build, not much more than a first-class bicycle, and when made in quantity can be made very much cheaper. He told me that he hoped to sell his American patents and asked me if I thought he could get $ 4000 for them. His plan was to build, in or near Berlin, a sort of flying rink, with an artificial slope which could be turned so as to always face the wind. Here people could come and hire machines and learn to use them, commencing with small elevations and gradually going higher up the slope, as practice gave them skill. He hoped to get people, particularly athletes, interested in the sport, for with a wide interest would come improvements. The present bicycle is not the work of a single man, but the result of years of experiment and thought given by many men. It must be the same with the flying machine. If the unfortunate death of the pioneer does not deter others from experimenting along these Lines, and it does not seem to me that it should, the results accumulated by him will not be lost and he will not have given up his life in a vain cause. He has made thousands of flights in safety and felt absolute confidence in his ability to control his machine in any ordinary wind, and his accident was merely one of those liable to come to anyone engaging in any of the popular outdoor sports.

Undoubtedly the danger element is greater in this sport than in most others, but with improved apparatus it can be made, in my opinion, as safe as tight-rope walking, which is really not so very perilous when you know how. Lilienthal is certainly the first man of modern times who has navigated the air for any distance without the aid of a balloon. Maxim's wonderful airship, so far as I know, has not yet been run in free flight, though developing astonishing speed and buoyant power on its track. The former practised soaring flight against the wind. Without any movement of the wings, the latter drives his aeroplane through the air by an engine and screws. Lilienthal had the advantage of being part of his machine, as it were, feeling every change of plane and instinctively correcting it with a motion of the body. He thus slowly acquired the skill necessary to keep the apparatus level with varying wind pressure.

The aeroplane at present is an unstable machine, requiring the agency of a human mind to keep it in equilibrium, and the necessary skill can be best acquired with small machines fastened directly to the body. I do not think that anyone who has experienced the difficulties encountered in keeping one of these small machines in equilibrium would venture to carry Mr. Maxim's aeroplane into the air, the balancing being effected by rudders put into action by opening or closing throttle valves. It would be, to my mind, like trying to ride a steam bicycle fifty feet high, perched in a small cab on top of the huge wheel, with a row of valves for driving and steering, without having had any experience with a small machine. The small machine is undoubtedly the one to commence with, and what Lilienthal's machine needs to increase the safety factor is some means of loosening things when struck by a sudden gust. I use this expression in a very broad sense, of course, and possibly the desired effect could be obtained by a ballasting device, but flying with the machine as it now is is like trying to sail a boat with the mainsheet fast. It can be done, but it is risky in squally weather.